Gyokusai: Smashing the Jewel of Japan

In Transit – June 1944

Capt. Lawrence Rulison, the commander of K Company, 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines, listened as his battalion commander, LtCol. Justice Chambers, briefed his company on the plan for what was ahead. The 4th Marine Division was now sailing as part of the Northern Troops and Landing Force, one of two task force groups under the command of the V Amphibious Corps that was underway for OPERATION FORAGER: the seizure of Saipan in the Mariana Islands. Alongside them was the 2nd Marine Division, now recovered from Tarawa, additional Army and Marine artillery battalions, and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit from New York designated as the overall operation’s reserve. The Kings of K Company, Rulison learned, were part of over 165,000 ground troops underway for the task, with D-Day set for June 15, 1944.

The overall goal of this operation was emphasized to the men as they listened, that once Saipan had been seized, along with Tinian and Guam to its south, the islands were to be converted into air bases for the Army Air Corps’ latest long-range bomber: the B-29 Superfortress. Once they had accomplished this critical mission, a strategic bombing offensive like that over Europe would commence against Japan. Additionally, it was hoped, the captured prizes could serve as an advanced submarine base as well, allowing America’s undersea wolves to have a much closer operating base as they strangled the enemy’s island homeland from the sea as well.

Not surprisingly, the Japanese were well aware of this too. Realizing the threat from both air and sea that the loss of the Marianas would pose, in September 1943 Japan designated a defensive line that ran from the Kuril Islands in the north, through the Marianas, to New Guinea, and then extending west through Malaya and Burma. The line was designated as Zettai Kokubōken, or the Absolute National Defense Zone, and it was specifically stated that its loss at any point along it would mark a major strategic reversal in the overall war. Any attempt by the Allies to breach it was to be immediately counter-attacked with massed air power and what remained of their still-forceful Combined Fleet, destroying any attackers and restoring this line.

Knowing that it was impossible to defend everywhere at once, and realizing that they had now lost parity with American strength, both in terms of quantity and technological superiority, this fleet was being held in reserve in the Japanese-occupied Philippines. But, they hoped, if the American Navy decided to extend itself to attack at any point along Zettai Kokubōken, a massive combined attack could perhaps bring about the decisive naval victory they had been seeking since their failed attempt at Midway two years before. This battle, Tokyo knew, was its last opportunity to protect its home islands. Should they fail, it was only a matter of time before the Americans arrived on their home shores.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, such a counterattack was exactly what Admiral Chester Nimitz was hoping for when he planned FORAGER, knowing that such a desperate attack would finally allow the US Navy the opportunity to destroy what remained of the Japanese fleet once and for all. As a result, the armada the Kings were sailing in, the one Japanese were determined to engage and turn the tide, was the largest yet seen in the Pacific – hungry for a decisive battle of its own. In a way, the Marines were serving as bait, although that was likely left out of Chambers’ briefing.

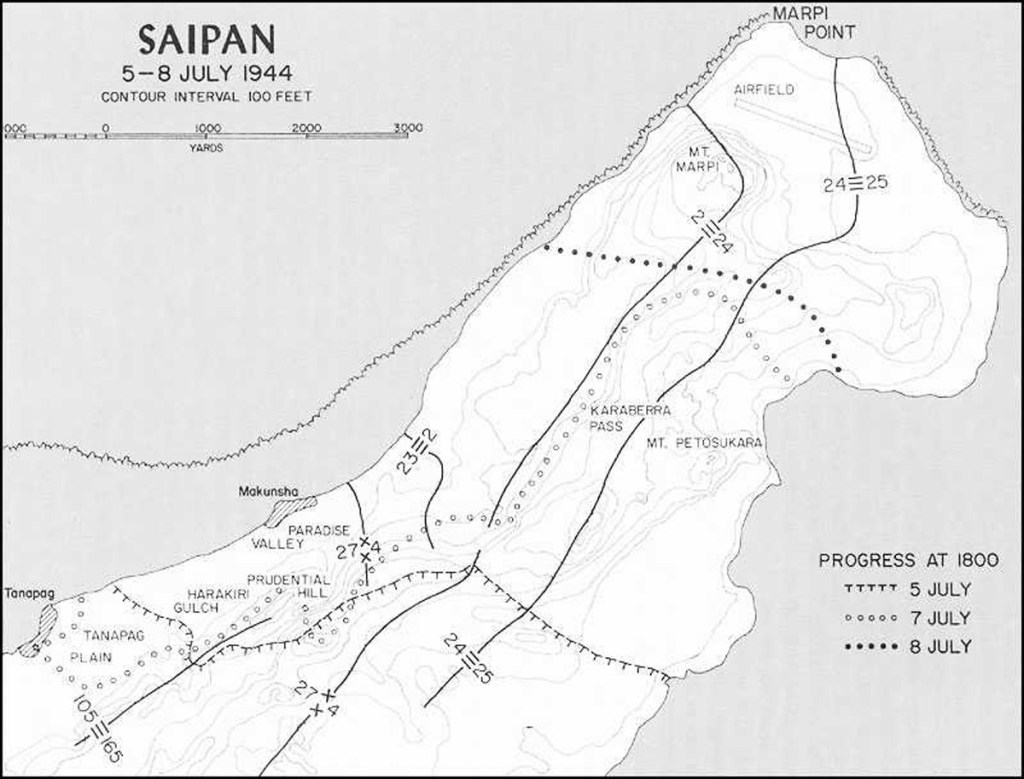

D+21 – 06 July 1944

Saipan

Three weeks later, a heavy downpour started pouring down on the exposed Americans across the island, drowning out any sounds nearby and screening all but the closest of movement from view. The landing and fighting across the rough terrain had been some of the worst yet experienced in the Pacific, but three divisions still had roughly a third of the island to go.

A week before, the Combined Fleet had indeed sortied out and clashed with the US Navy, only to suffer one of the most one-sided defeats in all of naval warfare. Dubbed the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot by the Americans, the Japanese suffered losses so great in both ships and aircraft, that the irreplaceable Combined Fleet had, in essence, been completely destroyed. For this, the Americans only lost one-hundred and twenty-three planes, two-thirds from ditching after empty fuel tanks, with only one ship seriously damaged. Not a single American vessel had been sunk. The Japanese could never hope to recover.

While the men on the front line were unaware, word of this defeat had just reached Saipan’s defenders, and they were just beginning to counter. The Japanese took advantage of poor weather, attacking at several points across the line. When the sun came up, hundreds of enemy dead laid out ahead of them, a large number only armed with crudely-made bamboo spears. Although they did not realize it at the time, these attacks were only diversionary, distracting attention from something even greater that was planned for off to the west.

The previous afternoon, the 105th Infantry Regiment, part of the 27th Infantry Division now responsible for the western portion of the front line, captured a prisoner. Sent back to Corps G-2 for interrogation, he, like many Japanese captured during the war, spoke freely to American intelligence officers, telling them of a large attack coming in the immediate days ahead. This report was taken down, analyzed, and then disseminated out to the divisions.

Late that afternoon, Marine LtGen. Holland Smith had visited the 27th Infantry Division’s headquarters, relaying to MG George Griner that they expected the attack to head towards him down the Tanapag Plain along Saipan’s northwestern shore. They estimated it would occur either that night or the early next morning, on July 7. Such attacks were not all out of the ordinary to the Soldiers or Marines by this point, and Griner replied that his troops were ready.

Not far away, another commander had readied his troops as well. Trapped and cornered, without hope of either a victory in the air or sea, Lieutenant General Saitō decided it was time to violently lash out rather than continue their slow death by attrition. Issuing his surviving troops their final order just days before, he laid out plans for one last operation, concluding his order with:

“Whether we attack or whether we stay where we are, there is only death. However, in death there is life. We must utilize this opportunity to exalt true Japanese manhood. I will advance with those who remain to deliver still another blow to the American devils, and leave my bones on Saipan as a bulwark of the Pacific.

As it says in the Senjinkun [Battle Ethics], ‘I will never suffer the disgrace of being taken alive’ and ‘I will offer up the courage of my soul and calmly rejoice in the living by the eternal principle.’ Here I pray with you for the eternal life of the Emperor and the welfare of the country and I advance to see out the enemy.

Follow me.”

Saitō then committed seppuku, his call to advance and deliver a final blow in defense of the emperor’s honor left to his subordinates to carry out. Hundreds of Japanese dutifully followed his orders however, and began emerging from caves and assembling around Makunsha village in the days since it had been distributed. Some of these were who had just hit the American lines in the rain the previous night.

While most of the Americans assumed the intelligence reports were just yet one more of similar such reports, one small team attached to the 27th Infantry Division’s intelligence section knew what was coming was far more than the typical “banzai” attack. At the head of this section was 2LT Benjamin Hazard, an intelligence officer who had grown up in Massachusetts with friends of Japanese descent, giving him an interest in their language and culture early on. This interest followed him to the University of California Los Angeles, where he continued to study Japanese at night at local adult education classes offered in town until the university began to offer its own courses.[1]

After Pearl Harbor, two Army majors had come through campus looking for “Americans of non-Japanese ancestry,” recruiting intelligence officers for the war in the Pacific. Intrigued, Hazard volunteered, dropping out of school two weeks shy of graduation to begin training. Now finding himself on Saipan, Hazard led a small language detachment comprised of himself and seven Nisei-American Soldiers, and something about the recent intelligence reports coming in caught his team’s attention.

A few days before, his section had interrogated a civilian working for the Japanese army that had just surrendered. Like the others, the man spoke freely, telling that the Japanese were preparing for an attack on July 7. But in this case the prisoner had used a particular word to describe these plans, something missed by the traditional intelligence officers in this and their other recent interrogations, something that immediately caught the attention of the Nisei: gyokusai. Hazard recalled:

“A gyokusai can only be ordered by Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo. It came out that they were going to engage in a gyokusai. This was not the same as a banzai attack. This is to attack until annihilation. That is, to keep fighting. [To] destroy as many as possible, and nobody is to survive. To die in honor. And literally, it means… ‘gyoku’ is ‘jade’ and ‘sai’ is ‘to smash – smash the jewel… [The] jewel being the army, and destroy it.”

The Nisei also noted that July 7 was the traditional Japanese festival of Tanabata, an adopted Chinese holiday that was celebrated in Japan for when “the spirits of the dead are supposed to return to Earth,” Hazard remembered, adding, “which is also a good time to die – you join your brothers.” Something the Americans had never seen before was coming, yet only this small handful of mostly Japanese-Americans even realized it.

Another prisoner had been captured and was interrogated on July 6, who again eerily used that specific term, setting off further alarm bells among the Nisei. This prisoner also stated that it was to commence at around midnight. Alerted, Hazard frantically tried to convince his superiors of what was coming, “but they didn’t give it the same weight that… the Nisei felt. They [the Nisei] knew.” Fully sensing the gravity of the situation – a situation that they themselves were also caught in the middle of – this small group of disregarded Japanese-American intelligence specialists were helpless to do anything about it.

The Nisei also knew that there was one word the Japanese never used to describe or order an attack: banzai. Aggressive Japanese human wave attacks were no different than what their grandfathers had done at Port Arthur decades before, but counter to beliefs that persist even today, such attacks were not specifically intended for every one of those involved to sacrifice their lives in its effort. Not unlike the aggressive and daring Marine amphibious assaults in the recent years, with potential for death or injury high, where most were willing to lay down their lives if need be, death for a Marine was never mandated. Neither was it for the Japanese.

While daring, the Japanese did hope to survive and continue fighting after their attacks, with survivors often retreating to regroup when unsuccessful. Seemingly suicidal to those on the receiving end, the Americans assumed that it was – the exact effect the Japanese were hoping to achieve. And when every one of the Japanese attacks included the screaming of “banzai!” as they charged forward, the term quickly became associated in American lexicon with suicide attacks.

This misunderstanding was to have dire consequences on Saipan, because Gyokusai, “is something different,” Hazard continued. “This is not just yelling and screaming and coming in. This is – they know they’re going to die. They come in singing. You could hear them in the distance, singing.”

But with banzai now so engrained, and because “that word gyokusai had not entered the vocabulary at all,” Hazard’s superiors could not – or would not – comprehend the difference. They continued to brush the intelligence officer off, even though the singing of suicidal men could now even be heard outside.

Throughout the early morning hours, the Japanese probed the hastily set American lines, discovering a sizable gap between 1/105 and 3/105 near the beach road. At around 0445 they struck there in force; many again only armed with handmade spears, some with even nothing at all. The Soldiers fired into these hordes as fast as they could, and bodies soon piled up so high in front of their positions that many had to move to new positions in order to have open ground in front of them before they could continue firing. Still even more came.

The commander of 2/105, MAJ Edward McCarthy, remembered seeing the masses coming forward at them vividly, describing it as something like out of a cattle drive scene from a classic western film:

“It reminded me of one of those old cattle stampede scenes of the movies. The camera is in a hole in the ground and you see the herd coming and then they leap up and over you and are gone. Only the Japs just kept coming and coming. I didn’t think they’d ever stop.”

Before long his battalion was overrun and McCarthy ordered a withdrawal, but heavy enemy fire all around quickly disorganized the attempt, nearly turning it into a complete rout. In order to prevent such from happening, he moved to a visible position where he could be seen by many of his troops, calling out and rallying them around him despite now being out in the open. Eventually McCarthy was able to rally a good portion of his troops to him, the group setting up a hasty defense as wave after wave of Japanese attackers crashed against their new position throughout the early morning.[2]

McCarthy knew many others from his battalion had been unable to see or get to him, left to fend for themselves most likely to their peril. There was nothing he could do about it. Before long, both his battalion and 1/105 nearby were completely overrun and cut off, the front line evaporating. The scattered few still alive were desperately left in a fight for their lives against a seemingly unending flood of crazed Japanese attackers, all hell-bent on finishing them off.

One of McCarthy’s Soldiers caught in these initial waves was 1LT Morris Seretan, the heavy weapons platoon leader of D Company, 2/105. He remembered his machine guns had initially devastated the first Japanese that had appeared in their sights, but soon their numbers overwhelmed even the thousands of rounds per minute his guns were firing. He similarly remembered it turned the fighting into something like out of the old American West, where groups of survivors could only circle into small pockets and try to hold out against swirling hordes of furious attackers. “It was just chaos that is unable to describe,” he later recalled.

Close to his company command post, Seretan and the survivors near him tried to make their way back towards it in hopes of finding others there. “As I was moving toward it,” he continued, “a grenade was hurled and shattered my left elbow.” Bleeding profusely, he had no choice but to keep going, but was soon hit again, this time in the groin from what was likely a bullet. This projectile was even more debilitating, penetrating through his hip and “leaving a gaping hole” in his buttocks on the other side.

Within seconds he was hit yet again, this time in his opposite leg, and he collapsed to the ground, now completely unable to walk. Despite the pain of his injuries, he knew that to stay there in the open almost surely meant a Japanese bayonet, and he knew his only hope for survival was to find a hiding place. “I tried to push myself and crawl to get into something where I could get some cover,” he remembered, pushing through the excruciating pain.

Spotting a disabled halftrack not far away, Seretan began pulling himself along the ground with one arm in its direction. In what must have felt like an eternity, he managed to finally reach it, but remembered the attempt had taken all that he had. “With my last bit of strength, I crawled underneath,” he recalled. That was the last that he remembered. He did not regain consciousness for almost an entire day. With such severe wounds, any Japanese that had passed by, must have assumed him dead.

Another caught in the gyokusai was SGT Thomas Baker, a member of A Company, 1/105. Severely wounded early on in the fighting, he refused evacuation, staying on the line until his ammunition had completely ran out. Once it did, he began using his rifle as a club, until even that became so damaged from use that it could no longer even serve that purpose. Now fading from loss of blood, a friend began to pull Baker to safety, but his rescuer was himself wounded before the two had made it more than fifty yards. Another Soldier then attempted to come to their rescue, but knowing his condition, Baker waved him off, not wanting anyone else hurt on his account.

He instead asked to be leaned up against a nearby tree and given a pistol. This was done and he was handed a .45 with only a single magazine. His comrades then departed, looking back to see him calmly facing the hundreds more oncoming Japanese, pistol in hand.

When Baker’s body was found the next day, it was still propped up against that tree. Those that found him noticed that his pistol’s slide was now locked back, indicating every one of its bullets had been fired. They also noticed that immediately around him were eight Japanese bodies, one for each of his rounds. For this and two other actions earlier in the battle, Baker was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Nearby was LTC William O’Brien, Baker’s battalion commander. Clearly seeing what was happening around him, he refused to allow the men around him to retreat, even though most of his units were by now been overrun and just fighting for survival in isolated pockets. Keeping the men nearby engaged, O’Brien personally walked up and down what remained of his lines, firing at the Japanese from a pistol in each hand. At one point he was hit in the shoulder, but refused to be evacuated, continuing to fire his pistols while a medic bandaged up the wound. Then, running out of ammunition, he grabbed a rifle from one of the wounded nearby, then yelled to the others around him to form a new defensive line, concluding his orders with, “don’t give a damn inch.”

As they moved to set this up, O’Brien noticed an abandoned jeep nearby, sitting there with a .50 caliber machine gun that sat unmanned and silent as a battle went on around it. A single round from the gun could easily tear through several men, and with the Japanese coming towards them in such densely-packed waves, the fire it could bring to bear was invaluable in such a moment. He ran over and jumped into the jeep’s rear area, stood behind the gun and began firing the weapon into the masses charging towards him.

“When last seen alive he was standing upright,” the citation from his Medal of Honor reads, “firing into the Japanese hordes that were then enveloping him.” Thanks to his leadership, 1/105 held. “Obie was one of the boys that day,” one of his Soldiers SGT John Breen remembered, “he died right on the frontline with us.”

Not far behind them was CPT Benjamin Salomon. Originally the 105th Infantry Regiment’s dentist, he had realized that there was far less demand for dental work in their present circumstances on Saipan, so he volunteered to serve as the battalion surgeon for 2/105 after theirs had been wounded by a mortar round roughly a week before.

In the early morning of July 7, Salomon was busy treating the dozens of wounded that were increasingly starting to arrive at his aid station. At one point he looked up to see a Japanese soldier bayoneting one of the wounded that was lying on the ground just outside his tent, so Salomon stopped what he was doing, squatted down, then aimed and fired, killing the assailant. He then set his rifle down, turned and resumed treating his patient.

Two more Japanese soon appeared at the entrance of the tent, but his medical staff were able to dispatch them without too much trouble. Moments later however, four more began crawling in under the tent’s canvas walls. Salomon ran over, kicked a knife away from one, grabbed a rifle and shot another, then rushed over and bayoneted a third. Turning to the fourth, he hit the assailant in the stomach with the butt of his rifle, then a wounded man nearby shot and killed the Japanese before the dentist-turned-rifleman could attempt another blow.

Clear now that the aid station was just seconds from being overrun, Salomon ordered the wounded to make their escape the best they could, then headed outside to try and buy them some time. He found a machine gun with four dead Soldiers around it, so ran to it and put it back into operation, bringing the weapon back to life and sending streams of bullets tearing into the oncoming attackers. That was the last Salomon was seen alive, but a good number of wounded and aid station personnel had been able to make good their escape with all the Japanese nearby either cut down or drawn to his fire.

When the aid station was cleared the next day, Salomon’s body was found still at the machine gun. He had been wounded at some point in the ordeal, and it was clear he also had attempted to move the gun to a better firing position before finally being fatally struck down. Twenty-four bullet holes were counted in the dentist’s now lifeless body, yet a total of ninety-eight Japanese dead were found strewn about in front of his position.[3]

One large Japanese group succeeded in finding an open gap, managing to advance over a thousand yards until finally running into the artillerymen of 3/10 Marines just to the southwest of the village of Tanapag. There they hit H Battery the hardest, forcing the Marine gunners to set timed fuzes so short that they burst almost as soon as they left their howitzers’ tubes, converting the cannons into large shotguns. Still the Japanese came on, forcing them to do the one act no artilleryman wants to even contemplate: abandoning their guns. One of these was 1Lt. Arnold Hofstetter, who remembered having no choice but to do so:

“Small arms and machine gun fire was heard to the front and right front at considerable distance at about 0300, July 7, 1944. No information as to source could be obtained. Later, the fire appeared to come closer and, since it appeared that the position might be attacked, the gunners were told to cut time fuzes to four-tenths of a second in preparation for close in fire.

About 0515, just as it was getting light, a group of men [were] seen advancing on the battery position from the right front at about six-hundred yards. It was thought that Army troops were somewhere to the front, so fire on this group was held until they were definitely identified as Japs at about four-hundred yards. We knew that our men manning the listening post were somewhere to the front, so the firing battery was ordered to open fire with time and ricochet fire on the group to the right. Firing was also heard from the machine guns on the left.

After the howitzers started firing, it sounded to me like [Howitzer] Numbers 3 and 4 were not firing enough, so I went to these pieces to get them firing more. I got them squared away and stayed with Number 4 until Japs broke through [a] wooded ravine to the left, and I heard that word had been passed to withdraw. The firing battery fired time fuze and percussion fuze so as to get a close ricochet. Some smoke shell was fired. Cannoneers were shot from their posts by machine guns and small arms… which interrupted the howitzer fire and finally made it impossible to service the piece.

The remainder of the firing battery fell back about one-hundred and fifty yards from the howitzers, across a road, and set up a perimeter defense in a Japanese machinery dump. This was about 0700. We held out there with carbines, one BAR, one pistol, and eight captured Jap rifles. Japs got behind us and around us in considerable strength. They set up a strong point in a point of woods to our rear. . . . About 1500, an Army tank came in from the right and got to the strong point and Army troops relieved us. I estimate that 400-500 Japs attacked the position. They used machine guns, rifles, grenades, and tanks.”

As Hofstetter mentioned, three Japanese tanks had appeared in the attack, one a Type 97 medium tank, another a light Type 95, and the last an odd Type 2 Ka-Mi, an amphibious tank developed by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Before the Marines had fallen back from their guns, the tanks made the error of bypassing the artillery positions, trying to keep driving further into the American rear. Despite being completely unprotected as bullets flew all around, the crew of one the howitzers bravely turned its gun completely around, depressed their tube to level, and sent a 105mm howitzer shell into the rear of the Type 97 from no more than fifty yards away. The impact of the high-velocity shell and its explosion tore the tank into pieces, leaving it a burning wreck.

Still, even this failed to stop the onrushing Japanese, and the Marines were forced to abandon their guns, including the one that now had a direct tank kill to its credit. In their haste, the Marines failed to disable their guns as they should have, lest the enemy turn and use the weapons themselves. But bent on death, their capture of the American guns was of little interest to the Japanese, who never bothered to use or destroy them themselves. As a result, the Marine howitzers were able to be quickly put back into action as soon as they were recaptured.

I Battery was hard hit as well, but slightly off to the side of the main Japanese avenue of attack, they were able to defend their positions until running out of ammunition. They then retreated further back to G Battery nearby, augmenting the defense there. Their battalion headquarters was not quite so fortunate. Located right behind H Battery, when the latter withdrew, the staff – all primarily logisticians and mechanics – took the brunt of the attack in full, mostly in hand-to-hand combat. Maj. William Crouch, the commander of 3/10 was killed in the ensuing struggle, along with one-hundred and thirty-five additional casualties suffered. Later they counted more than twice that number in Japanese dead around the command post area.

Not far away were the gun positions of 4/10. Similarly off to the side of the Japanese attack, they were able to hold without issue, killing roughly eighty-five attackers as they attempted to pass by. But one of their Marine gunners, a Tarawa veteran named Pfc. Harold Agerholm, knew that much of the other battalion had been overrun, and any survivors out there were now in desperate shape. Despite these men all likely total strangers, he volunteered to go and help, leaving his relative safety and running out into the fray before him.

Finding an ambulance jeep, he drove it by himself through where the Japanese had attacked to find and rescue any American he could. Despite the enemy still all around, for over three hours Agerholm made the trip back and forth through the Japanese to where 3/10 had been, driving as fast as he possibly could as bullets snapped close by for just about every yard he traveled. Each time he did, he came across desperate and wounded men that had been left behind in the chaos, loading each of them up and driving them back to safety.

Agerholm’s luck only managed to hold out so long. On what became his last trip he ran to rescue two wounded Marines that he had stumbled across, when a Japanese bullet finally found its mark, mortally wounding him. Later it was realized that forty-five wounded men had been safely evacuated thanks to Agerholm and his jeep, all likely strangers from a completely different battalion, but all still fellow Marines. Agerholm, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the third awarded for heroism above and beyond the call of duty during the gyokusai.

The surviving Japanese then reached the headquarters of the 105th Infantry Regiment, roughly another five-hundred yards further. Here the gyokusai finally ran out of steam, as the Army headquarters personnel defended their position fiercely from previously-taken Japanese positions. It took several hours of close fighting in the dark, often hand-to-hand, but eventually the few surviving Japanese withdrew. Two other smaller attacks occurred that morning, including one against the Soldiers occupying Harakiri Gulch nearby, but each of these were quickly dealt with.

As daybreak finally appeared, bringing with it an immense sense of relief, the two cut off Army battalions were exhausted, out of ammunition, and down to about a quarter of their strength. Many more were missing somewhere out in the plain. Realizing that the attack had carried long past them, these various pockets instinctively began to move back to find other American units, carrying and dragging wounded comrades that they refused to leave behind.

At the same time, many of the Japanese survivors were attempting to move back towards Makunsha, resulting in running surprise clashes between them throughout the morning, but eventually the surviving Soldiers were able to coalesce into one large group. Realizing there was no hope for escape in their condition, they set up a defense around Tanapag, fighting off additional attacks long into the afternoon.

CPL Wilfred “Spike” Mailloux was a rifleman in B Company, 1/105 and was one of the fortunate ones to have survived until they withdrew to Tanapag. “I was scared as hell,” he recalled of the initial attacks, “when you hear that screaming – ‘banzai!’ – who wouldn’t be?” His company had fired their machine guns so frantically that before long all of their barrels had overheated. All of their rifle ammunition was exhausted soon after as well. After that he remembered, everything just “became a running street brawl.”

Eventually Mailloux made it back to the Tanapag perimeter and joined the growing mixed group. Put out onto the line, at one point a Japanese soldier ambushed him, stabbing him in the thigh with his long bayonet. “I got hurt real bad,” he recalled of the encounter, but for some unknown reason the Japanese soldier did not continue his assault and finish the helpless American off.

Mailloux then collapsed into a muddy ditch, where he soon passed out from loss of blood. Sometime later, SGT John Sidur, also of B Company, happened by and saw someone lying there in the mud. “I didn’t know who it was,” he remembered of what he saw lying there, “I just thought, boy, he looks familiar.” Eventually he recognized the face as someone from his hometown back in New York. Sidur quickly hauled Mailloux off to safety and medical aid. Living close to one another for the rest of their lives, Mailloux and Sidur remained lifelong friends to the very end.

Nearby was a 37mm anti-tank gun, manned by Soldiers from 2/105. They had been firing canister shot after canister shot into the hordes of Japanese out ahead of them, tearing gaping holes into the onrushing throngs. Throughout the course of the day however, the gun’s crew had steadily been picked off, making its operation much more difficult. Yet each time it happened another man stepped in and took his place, keeping the gun in action. “As they were killed, they were rolled aside by others who continued to man the piece until they were killed and they were rolled aside,” Hazard remembered after walking by. He counted eleven American bodies next to the gun, but as he moved about a hundred yards further, he spotted a dike piled full of Japanese bodies.

At around noon, an American artillery barrage mistook the remnants of the two Army battalions that were clinging on for survival around Tanapag. Friendly rounds now impacting around them, many of the already battered men could take no more and began running out into the water in hopes of escape. American destroyers thankfully sent boats in to pick them up before they drifted out to sea, the Sailors onboard learning firsthand the plight of the clearly shaken men.

At about the same time, two battalions from the 106th Infantry were ordered to counterattack into the area and rescue any they could while clearing out the Japanese that were still active in the area, but the going proved slower than had been hoped. Facing tough resistance, the 106th Infantry was only able to move far enough to relieve the gun positions of the still-beleaguered 10th Marines by day’s end, but could not make it all the way to the beleaguered men at Tanapag. Amtracs and DUKWs were then sent in to evacuate these survivors, finally getting them all out at around 2200.

Although unable to hold against such a massive attack, the two greatly outnumbered battalions had heroically continued to resist in their various pockets against thousands of Japanese that had surrounded them, exacting a heavy toll and leaving hundreds of their dead scattered across the Tanapag flood plain. By the time it was over, both the Army battalions had been completely decimated, suffering nearly a thousand casualties between them, including just over four-hundred killed. As the day drew to a close, both effectively ceased to exist as a combat force.

The 27th Infantry Division’s artillery alone had fired 2,666 rounds in just the first hour, their crews desperately feeding their guns as fast as they could without pause in an attempt to save their comrades. The Marine artillery added hundreds more shells of their own, firing just as earnestly even while at times having to simultaneously defend themselves. Both guns and gunners had given every last ounce of strength they had, loading the sixty-five or ninety-six pound shells into cannon breaches unceasingly until things finally quieted down. In so doing, they had played a major role in stopping the gyokusai. Between their fires and the desperate yet truly heroic defense of the Soldiers and Marines caught in its path, somewhere between three and four-thousand Japanese dead were counted where their attack had occurred.

Japan’s final act to maintain Zettai Kokubōken, its Absolute National Defense Zone, had been horrific; carried only as far as it had by the weight of human numbers. Although only succeeding in a brief disruption to American operations, all at a massively disproportionate cost compared to the ultimately inconsequential losses suffered by the Americans that morning, the gyokusai of July 7 marked in essence the end for the battle for Saipan.

More importantly, it signified the end for the Japanese nation as a whole; for in their own words, it marked a major strategic reversal in the overall war. Really it marked the beginning of the end. In both the air and now on land, the jewel had indeed been smashed. And doing so had accomplished virtually nothing.

Starting out as normal that morning, word of what had happened only reached the Kings of 3/25 on the opposite side of the island at around 1400. When it did, the 25th Marine Regiment ordered all units to hold their present position, wanting to see if assistance was going to be needed for what was still an unclear and tenuous situation. Accordingly, the battalions straightened up their lines and organized for defense.

Meanwhile, Chambers was curiously summoned back to regiment. “Batch [Col. Merton Batchelder] said that division had called and wanted to know where the third battalion was,” Chambers remembered being told when he arrived. Even the division clearly knew who to call on when most needed.

The regimental commander had told his superiors that Chambers’ Raiders were then committed and were in pretty rough shape, so could not be used to assist. Still, they told him to have Chambers hop in a jeep and conduct a reconnaissance of the area, just in case. Doing as ordered, Chambers soon found himself on the opposite side of the island, driving along the coastal plain where the gyokusai recently occurred. As he did, he took in the gruesome sight all around him. “I never saw so many Jap bodies in one restricted area.”

[1] After the war broke out, his instructor at UCLA and several of his Japanese friends were all sent to internment camps. A Japanese-speaking instructor of Korean descent had to be brought in to finish out the semester.

[2] For his leadership in rallying his men that morning, MAJ McCarthy was awarded the Silver Star.

[3] At the time, medical officers were barred from taking up arms by the Geneva Convention, and so the several requests to award him a medal for valor were repeatedly denied. In 1998, Dr. Robert West, an alumni of where Salomon had studied, the University of Southern California School of Dentistry, submitted a request for this regulation to be waived and for Salomon’s heroism to finally be recognized. On May 1, 2002, President George W. Bush presented CPT Salomon’s Medal of Honor posthumously to Dr. West in the White House Rose Garden.