大日本帝国

Dai-Nippon Teikoku: The Greater Japanese Empire and its Road to War

Not unlike the rest of the world prior to European ships arriving off their shores, pre-industrial Japan was a tribal society, with various clans led by feudal lords known as daimyos, constantly warring and allying amongst themselves for centuries in their attempts to control power. In the eighth century, the prevailing clan at the time was the Yamato clan, but various clan warlords known as Samurai continued to vie for political power. Powerful military dynasties grew up around these warlords and their clans, eventually removing the Yamato clan from power in the twelfth century. Political control then exchanged hands over the course of the next eight-hundred years, the head of each of these ruling clans designated as the Shogun.

Warfare naturally was frequent up and down the Japanese island chain, as the various clans took every opportunity they could to usurp power and become the next Shogun. Through this constant combat, the Samurai increasingly became a distinct warrior class, one whose battlefield courage was revered and whose devotion was expected to the point of willingly laying down their lives as proof of their loyalty. Not all that dissimilar to the beliefs espoused by European knights on the other side of the world, falling short in these attributes was unthinkable, with suicide expected rather than living with such a dishonor.

As Europeans began to arrive in the late 16th Century, unlike most, the Japanese reacted by turning them away and virtually, albeit not completely, closed off their society to any outside trade, influences and foreign contact. This allowed the feudal Japanese society to continue on for over two more centuries, living isolated in an ancient culture that the world had long since passed by. That was until a United States Navy detachment arrived off the Ryukyu Islands in the Spring of 1853 with specific orders from President Millard Fillmore to open up the reclusive nation for trade and the establishment of coaling stations, by force if necessary.

Ordering a detachment of Marines ashore on present-day Okinawa, a frumpy American naval officer named Commodore Matthew Perry had the group come ashore in a ready posture, immediately lining them up in formation and practicing drill, displaying their modern military uniforms, equipment, discipline and prowess to locals that watched on in astonishment. Promises not surprisingly were quickly made to open trade. Re-embarking, Perry then made his way north, entering Edo Harbor on July 8th with four ships, deliberately bypassing harbor defenses while firing off his own cannon in salutes. Their attention caught, local Japanese officials came aboard, but Perry refused to meet with them, stating that he had a letter from the President of the United States and only would meet with an equivalent-level official.

Two days later the Japanese tried to redirect Perry to Nagasaki, but he again refused their conduction. His reply left no question of his resolve, stating that unless he was given access he would land his troops ashore, march on the capital of Edo and have them deliver the President’s message, weapons at the ready. While awaiting an answer, he continued to flex and show force, communicating in no uncertain terms that any attack on his detachment or ships would quickly result in Japanese destruction. Reeling at this bold surprise, and knowing they had nothing with which to defend against this force, the Japanese backed down, allowing Perry to land and deliver the letter on July 14. As he handed over what was in essence demands to open up to trade, Perry promised to return the year following for a response.

Hearing that the Russians were soon now going to attempt the same type of diplomacy in Nagasaki, and with the British and French demanding to accompany him upon his return to ensure fairness in diplomatic outcome, Perry decided to return to Japan early. Arriving again on February 13, 1854, this time he brought with him ten ships and even more troops, no doubt playing a large part in him successfully securing an agreement on March 31 to open two ports for any necessities required by American ships. Also in the agreement was a promise of satisfactory treatment for any stranded American sailors, along with approval for the establishment of a consulate in the country, a seismic shift in opening for international access. Perry departed leaving numerous gifts, to include a miniature steam locomotive that had the Japanese captivated almost as if they had seen a flying car, but also served the dual purpose of clearly showcasing technological prowess the West had over them. Before long other world powers had signed similar agreements, and the doors to the hermit kingdom of Japan were finally opened.

Isolated as they were, the Japanese were not completely unaware of what was happening in the world around them. By the mid-19th Century, the arrival of Europeans meant a sequence of events that all tended to follow a similar pattern: the seemingly harmless initial acceptance of traders and missionaries, this eventually leading to declarations of spheres of influence as a particular nation attempted to keep out its rivals. Sometimes declared, sometimes not, as these foreign nations fell under the control of the European power, and it usually was not long before the unwitting locals were turned into some degree of colonial subjects. Having seen this happen virtually without exception across the globe, combined with the technology and military might that was far beyond their present means that they now saw, the Japanese smartly realized that their only means of national self-preservation was to join the modern world. More specifically, this meant industrializing and becoming a power themselves equal to the Europeans.

While this process began, the weakened Tokugawas attempted to reaffirm their control, but several other Shogunate quickly jumped on the opportunity to usurp it, or at least share it in the interim. In short, in order to retain some form of control, power was handed to Mutsuhito Sachi, later Meiji-tenno, on November 9, 1867, thereby “restoring” power to the emperor. This modernization and warring period, collectively known as the Meiji Restoration, marked a turning point for Nippon, the Land of the Rising Sun.[1] The new Meiji government now moved to consolidate political control, creating bureaucracies and systems now at a national level like those seen in the outside world. One of these moves was to organize a national Army, deliberately stationing its members away from their home regions, and then, following the official dissolution of the clans in 1871, implementing universal conscription systems mirroring those in Europe.

Naturally, this transition took years, especially the Army attempting to inject a national identity into its ranks. To do so, officer schools were established to create a professional officer corps, removing what had been the sole responsibility of military leadership from the samurai. The enlisted received their share of indoctrination as well, the government this time taking the example of the elite samurai and their “way of the warrior” code Bushido and applying it now to the average rank and file. Expanding membership in the samurai to all soldiers, much to the chagrin of those who were actually members of that caste, the Tokuho soldier’s code was established in 1872, detailing the seven virtues of a soldier in the Japanese national army: loyalty, unquestioning obedience, courage in battle, the controlled use of physical force, frugality, honor and respect for superiors.

Although in later years these virtues were to be manipulated, even the poorest of Japanese farmers that found himself in uniform was now imbibed with the idea that he too was expected to uphold the legacy of the samurai. Not all that dissimilar from the moral ideals held in the West at the time, this duty was expected to be upheld at all times, even if it resulted in his death. It took time, but soon a class began to emerge at a national level that was just as fiercely loyal to the emperor and the central government as the threatened and dwindling samurai were once to their clans.

Given the emperor’s divine lineage, the soldier’s personal code soon took on a spiritual aspect to it as well, its tenants becoming sacred obligations. This took hold quickly within the highly religious recruits from the rural areas, those now making up the majority of the new and growing army and navy. Meiji himself sought to build on this ideology, promising to worship annually at the Yasukuni Shrine, a memorial in the renamed capital city of Tokyo, built in honor of those that died in his service during the Boshin War. This memorial’s purpose soon expanded to include any that had died in his service, promising they would all meet again in the next life, regardless of clan origin. Before long, this new mythical heaven at Yasukuni soon took on a fervor amongst the emperor’s soldiers not all that dissimilar to Valhalla or the Fiddler’s Green.

Naturally the samurai did not take to these changes heartily. The discontent of this warrior class, a group that still commanded the loyalty of no small number of men within their clans, was of great concern to the Meiji government. Attempting to further cement their control, in 1876 they forbade the wearing of swords, an effort not only intended to disarm their opponents, but also took away their most prominent display of status. A short time later, with a national army emerging, there no longer was the need to depend on the samurai for the traditional raising of armies on behalf of the shogun, so the government decreased their centuries-old promise of annual stipends, and paid out the little they did give them in the form of government bonds. A birthright duty owed in their eyes, the samurai fumed.

This resulted in a civil war of sorts in February 1877, samurai fighting against soldiers of the new Nipponese national army, now armed and organized on Western models. They first engaged a group of 4,000 of this new army defending Kumamoto Castle, along the road to Tokyo. Perhaps to the surprise of all parties involved, the vastly outnumbered conscripts, imbued now by their own version of samurai tradition, held out for nearly two months against real samurai three times their number. A relief force was sent, and although losses were heavy, the modernized weaponry and tactics they used eventually won out. As the Satsuma Rebellion concluded in September of that year, so also concluded the last true battle of the centuries-old samurai. In its ashes a new version of the tradition was born: one based on the same virtues and ideas, but expanded to include all classes, all now loyal to the emperor and the singular nation of Japan.

Industrial and military modernization in the European style had clearly proven its worth. Much more had to be done, and the Japanese spent the ensuing decades building and training further, much of that thanks to European trainers and officer exchanges, along with foreign purchases and trade agreements. This effort also included the building of arsenals and manufacturing, gradually giving the Japanese the ability to supply almost everything needed armaments-wise for themselves by the turn of the century. Further, the dramatic German victory in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 showed the world the value of a professional military general staff, and the Japanese quickly adopted a similar model for themselves as well. Theirs however remained completely separate from any form of civilian oversight or control outside of the emperor. Innocent at first, the move was to have significant repercussions half a century later.

Unlike the rest of the non-Western world, Japan had the foresight to see what was going on across the globe, watching as the world around them increasingly continued to be dominated by the Chinese, and then in turn by the major European powers as they came on the scene in more recent years. Accordingly, Japan decided to make “herself strong in response to an acutely painful recognition of her vulnerability to the West.” [Soldiers of the Sun, 58] As a result, as the calendar approached the twentieth century, the Japanese were by far the strongest and most proficient non-Western military power in Asia, although they remained untested.

Most immediately alarming was the events unfolding on the Korean peninsula, its southernmost point only 120 miles from Japan’s nearest shores. Any non-Japanese influence that found a home there thus posed a significant threat, one that could not be tolerated. Initially the Japanese just jockeyed for influence, but after the Chinese sent troops to the peninsula in response to a local revolt in June 1894 – at the Korean government’s request – Japan could not allow another to cross what they had declared as their “line of advantage.” Troops were sent over, and before long clashes between the two non-Korean nations occurred, with war finally being officially declared on August 1.

Lasting until April of the following year, the modern Japanese army decisively defeated the Chinese at every turn, forcing them to plead for peace. Their demands were initially heavy until three European powers, France, Germany and Russia, stepped in and forced them to soften their mandates, the latter of the trio even threatened force. Cornered, the Japanese settled. The Chinese agreed to recognize Korean “independence” and handed Formosa and its surrounding Pescadores Islands over to their former foes.[2] In exchange, the Japanese agreed to return the Liaodong Peninsula and its strategic ice-free port of Port Arthur, the latter seized only after suffering extremely heavy losses. The port was the jewel in the crown of what they sought in securing Nipponese – not European – influence; one they had paid a steep price for, yet had been forced by the Europeans to give up. The sting was to prove lasting.

Modernization efforts had now been proven outside their borders, but the victorious Japanese smarted at the lot they had been forced to swallow down by the Europeans, frustrated not only with the fact that they even had a say in the matter, but also knowing that the same hard-won territories they had just returned soon would be pulled into the influence of these same Europeans. The experience only reinforced Nipponese distrust of the West, the misgivings that had forced them into this modernization drive in the first place. And with such a strong notion of honor at the center of their cultural values, any previous suspicions now were replaced with feelings of outright anger, the interloping European powers now seen as a very real threat. Unwilling to ever let such an insult ever happen again, Japanese defense budgets doubled and tripled in the years that followed, expanding and modernizing even more toward a military that one day could one day stand toe to toe with the Europeans.[3]

Nippon did not have long to wait. Even as the proverbial ink on the Treaty of Shimonoseki was still drying, the Japanese-resistant Korean king sought to fill the vacuum the Chinese had left with someone else. Through his daughter-in-law Queen Min, the Koreans turned north to a nation who desired access to an ice-free Pacific port, finding a willing friend in Russian Tsar Nicholas II. The Japanese response to this political courtship did them no favors with Koreans in this battle for influence, their soldiers in Seoul assisting pro-Japanese activists in breaking into her palace and murdering the queen on October 8, 1895, then dragging her body out to a copse of trees outside and burning it. The Koreans naturally turned to the Russians even more heartily in response, and any and all Japanese hopes for complete domination of influence on the peninsula were quickly gone.

The Koreans were forced to settle for an agreed upon division of influence between the two nations in 1896, but the cash-strapped Chinese had agreed to allow the Russians to build a direct rail line through Manchuria to Vladivostok in exchange for funds to pay off indemnities still owed to the Japanese from the previous war. Before long the Russians had not only extended that railroad south into Port Arthur, along with also securing a lease for the use of its port. Meanwhile other European nations continued to solidify and expand their influence throughout Asia and Oceana, only exacerbating Japanese fears even further.

A successful joint venture with seven European powers in the summer of 1900 to suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China gave the Japanese some hope for an equal seat at the table in the future, but those hopes proved short-lived. As the others began withdrawing their garrisons by April 8, 1903 as agreed upon, the Russians dragged their feet and remained. Now Japan’s worst fears had come true: an encroaching European nation right on their border, both in Korea and Manchuria. The moment they had anticipated had come, and Nippon delivered an ultimatum to the Tsar on January 13, 1904. The Russians demurred, lifting their nose at what they saw as second-rate non-Europeans, foreign amateurs not to be taken seriously like all the others.

Things finally boiled over in early February, when the Japanese launched a surprise night attack in the harbor, severely damaging three capital ships, including the most powerful battleship in their fleet, Tsesarevich. War had already been officially declared several hours before, but the actions had been so swift, even in the world of the telegraph, that no word of it had made its way to the Russian forces in the region when the Japanese ships appeared and opened fire. Still, the Japanese were not strong enough to effectively storm or blockade the port, and so decided to lay a trap in hopes of luring the Russians out. Feigning a retreat, they laced the waters behind them with mines as they departed. The Russians decided to give chase, and two battleships fell victim, one of which was the newly-built 11,000-ton Petropavlovsk that slipped under the waves almost instantly, taking the majority of her 679-man crew with her to the bottom. The other was towed back to port. In the age of the battleship, with limited repair capabilities locally and without any hope of naval reinforcement in Europe, the initial Russian losses were significant.

The Russians now bottled up in Port Arthur, soon finding themselves under siege by land from Japanese troops that had come ashore nearby. Realizing time was most likely not on their side, the Japanese spared no expense in casualties, turning the siege into what was more of a constant assault. Hurling thousands of troops at the surrounding Russian defenses, they finally captured the key hills that surrounded the port on December 5, emplacing heavy guns and taking the anchored and now vulnerable fleet below under fire. Several more Russian forts had to be destroyed by mining over the weeks that followed, but exactly one month later, the Tsar’s forces within Port Arthur asked for surrender.

While usually in siege battles the casualty figures of the besiegers remain comparatively light, the impatient Japanese lost nearly double that of the Russian defenders in the engagement. Such was to become a familiar pattern for them in the remainder of the conflict as well. In the battles to the north, out in the open ground that was the approaches to Manchuria, the Japanese repeatedly proved expert at deception and outmaneuvering the Russians. Yet whenever they ran into a difficult position, their solution was always to resort to aggressive mass infantry charges, and their subsequent losses were staggering. In what have should been a foretaste for what the next battlefield was to look like in the upcoming Great War, with modern machine guns and massed artillery devastating the ranks of charging infantry that now belonged to a bygone era, the Japanese almost completely bled their army dry in their successes.[4]

With their army depleted to critical levels and their still-industrializing economy now turned upside down by the war, fortune handed the victorious Japanese the card they desperately needed. As word came of the Russian Baltic Fleet finally arriving in Asia in the Spring of 1905, the commander of the Japanese Imperial Navy, Admiral Togo Heihachiro, anticipated the Tsar’s ships would decide to cross through the restrictive Tshusima Straight between Korea and Japan. Expertly maneuvering his own ships in the battle that followed, Togo sank seven opposing battleships, capturing four others and virtually all the remaining auxiliary ships in the Russian fleet. With the war increasingly unpopular at home, the Tsar had pinned his last hopes on the Baltic Fleet, and now with its catastrophic loss, Nicholas II lost completely heart. Envoys soon arrived, meeting equally-eager representatives from Nippon, who signed a final peace treaty on September 5, 1905.[5]

Not since ancient times had a non-Western society completely checked and won an extended war against a European power. Indeed, the Japanese had defeated the Russians in every major battle during the Russo-Japanese War. Thanks to their foresight and modernization efforts in the years preceding the conflict, Japan had done what no other nation across the world had accomplished: halt Western expansion into what they deemed as theirs, preserving their complete national independence. The human costs were horrific, but the Treaty of Portsmouth gave Japan the previously-coveted Liaotung Peninsula and Port Arthur, along with control of Korea and the railroad networks in between. Perhaps even more importantly, the Japanese victory caught the attention of the rest of the world, giving Japan a degree of international respect that they so much desired. For the next several decades that followed, Japan now had a seat at table with the world powers over concerns in Asia. Again, the first nation in history to have ever truly had such a status.

With their own interests in the Pacific, the attention now gained by the Americans was not necessarily a positive thing, and suspicions born in these years would only continue to grow in the decades ahead. American concerns were not unwarranted, for whereas previously the Japanese had only sought to defend their interests at home, now their thinking and interests began to shift outwards. Independence and relative equality secured, Imperial Japan now began to look out at the broader world – and their place in it – their supremacy thus far now starting to shift their thinking towards becoming a colonial power themselves. It was here, in the success of the Russo-Japanese War, that the idea of Dai-Nippon Teikoku was truly born.

Although not really involved, the Great War in Europe did however open Japanese eyes to the realization that despite the great leaps in modernization that they had made, efforts that had brought them such great success in their most recent war, the great evolutions in warfare brought about by the conflict caused the European powers to considerably leapfrog the Japanese in military technology and industrial capacity once again. Any conflict they might face in the future, Nipponese military leaders quite aptly realized, would be fought on a much greater scale, requiring the mass mobilization of the nation’s entire populace and resources. In the latter category, Japan knew it was still lacking. Increasing industrial capacity to parity with the West would take considerable time, and even before that, their access to the raw materials necessary to equip an army in the 20th Century was only a small fraction of that of their perceived foes. Unwilling to exit this self-imposed race, Japan therefore only had one recourse: to control and export the needed resources from China.

Ironically, active participation in support of their ally in the First World War might have helped the Japanese completely avoid the friction with the West that led to the Second, but this was not to be. In the aftermath, not only were relations with Great Britain soured, Japanese enterprises within China also soon put them at odds with the nation that had emerged from the war as the world’s clear industrial powerhouse – the United States. Not only did the Americans have interests in China and the Philippines as previously mentioned, the war also was a financial boom for the new world power, and the Americans began directing much of this wealth towards their navy.[6] Russia and even Great Britain were one thing, but the United States however was something completely different. Yet now even the world’s greatest potential power was added to the Japanese list of threats on the horizon.

Then came the Black Thursday stock market crash in 1929 with the Great Depression following in its wake, causing severe challenges and disruptions to be felt across the globe for over a decade. Western attention now turned primarily toward focus at home, with far less concern given to the Japanese as they jockeyed for control of remote parts of Asia thousands of miles away. Although it felt the effects of the Depression as well, Japan knew it had a small window if it chose to expand its territory and secure some of the resources it needed without any foreign interference, but they knew they had to act quickly.

The Depression also combined this window of opportunity with desire. The years of scarcity and poor economic growth caused the rise of ultra-nationalism throughout the globe, to include Japan. With no end of the economic difficulties in sight, extreme political change seemed the only answer to many, and in Japan that extremism quickly found a home within the already scheming and nefarious professional military circles. With the shogunate disdain for civilian leadership still festering among them, many senior officers felt that increased military influence and even control was the only way to lead the nation through its economic troubles. Soon the Cherry Blossom Society was founded, with radical military officers actively looking and plotting for opportunities to usurp power.

The military extremists only had to look as far as Manchuria to find the fuel needed to stoke their fires. In addition to the threat the Russians still posed there, the Chinese had regained their feet and started to flex their muscles a little more. Despite this flex taking place within the Chinese own borders, their moves still were seen as a challenge to the Kwantung Army, the Japanese garrison that held their occupied regions. While there were some peacemakers in senior Japanese political leadership at the time, Japanese societal norms allowed for far looser military control from Tokyo than most Westerners typically are used to, freedom that these rogue officers in China sought to exploit.

During the night hours of September 18, 1931, these extremists took action, detonating explosives near a railroad track before an oncoming Japanese train. Damage to the track was minimal if any, and no Japanese were harmed or rail traffic disrupted. However the “victims” of this unprovoked attack just happened to have troops standing by at the ready to attack the nearby village of Mukden, who stormed in and seized the town, killing no small number of the Chinese garrison there before the sun rose.

Although Tokyo attempted to contain the incident, the Kwantung Army continued to move. Despite no authorization from the emperor, it then invaded Manchuria, with units from Korea answering their sister-army’s call and joining in. In the five months that followed, the Chinese were never able to significantly delay or defend at any point, and the Japanese government felt compelled to go along with and allow the army to continue in its successes. By the time they had finally run out of steam, Japanese forces had captured the northeastern-most corner of China, a strategically-vital area made up of hundreds of thousands of square miles. Despite staging Chinese bodies near the railroad attack site for the world to see, the United States responded by announcing in January 1932 that it would not recognize any Japanese puppet government established in any of the seized territory. The League of Nations followed suit shortly after. In response, even though its political leadership was still not fully clear on what had even caused the Mukden Incident in the first place, Japan responded by officially withdrawing from the world’s first international peace organization in March 1933.

The Asian world was now generally split between two parties: one a group of foreigners seeking to maintain their longstanding global dominance and influence; the other Asian, wanting to expand their influence and territory, indifferent to what the former thought but driven to prepare to defend against them. From each perspective, neither had any reason to act other than they did. So, while the eventual attack on Pearl Harbor came as a surprise, the collision of the Japanese and the Western powers was now obvious and inevitable on their current courses, more a matter of when than if. And between them lived millions that had no say whatsoever in the matter, millions forced to suffer from its effects.

The Japanese knew their second push at modernization was to take time, but changes in tactics and training could be incorporated more immediately. No doubt a product of their resource-constrained environment, Japanese army organization remained based on and around the foot soldier, not unlike most armies of the period across the globe. Anticipating that their most likely future conflict was to come somewhere in the vast regions of China, Japanese training and doctrine called for formations that were light, highly-mobile and relatively easy to sustain. Fitness therefore was seen of paramount importance, with the average formation expected to be able to march nearly three-hundred miles in less than two weeks, far outpacing what they expected their Chinese opponents to be capable of and thus allow them to maneuver deep behind them into their vast territory.

When battle was enjoined however, they counted on a repeat of the aggressiveness seen in the intense frontal attack tactics that had defeated the Russians at Port Arthur a generation before and easily scattered the Chinese more recently. Unflinching discipline down to the very lowest ranks therefore was seen as essential to accomplishing any difficult task they may come up against. A decade of this training and mindset would pass before war was enjoined with the West, and although their equipment only modernized somewhat in those years, the enemy the Allies were to soon find themselves facing were the direct product of this doctrinal thinking.

With troops so hardened, aggressive mindsets like this could not be left sitting idle for long. This, combined with a rogue officer corps that only somewhat even bothered to hide its disdain for its civilian leadership, the Japanese army of the 1930s was an absolute powder keg. A murderous Imperial Army coup on February 26, 1936 was their next attempt. The move failed to reorganize the government, but struck such fear into any surviving civil leaders that the Army came away feeling even more emboldened to act independently and dictate national foreign policy. In the months that followed, their focus for such policy remained aimed toward China, who they saw as their most likely threat, and also their easiest opportunity. The Chinese naturally were still fuming at the vast expanses of territory that had been outright taken from them, along with the Japanese troops that were elsewhere on once-Chinese soil, and so tensions only continued to brew.

It did not take long. That spark set off the powder keg came on July 7, 1937, after a small Japanese detachment out on night maneuvers took a pause near a small bridge for a rest. As they did, several shots rang out toward them from out of the darkness. In the chaos that ensued, one Japanese private from the group was found missing. The soldier’s commander demanded to be able to search the nearby Chinese-held town of Wanping for his man, and moved on it in the morning, even though by the soldier by then had been found.[7] Given that this small bridge, named after the Venetian explorer Marco Polo, was key to any advance toward the major city of Peking, it is unlikely that any serious words of restraint came down from higher echelons.[8]

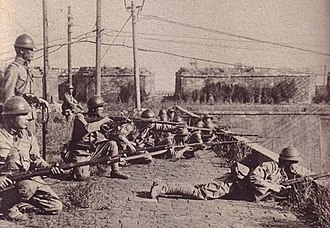

Both sides seemed to be at a heightened level of readiness this time, as reinforcements from each began to almost immediately arrive during the tense hours that followed. Then, as the sun rose, the Japanese troops moved toward the town and began to surround it. Ordered to hold the key bridge at all costs, the Chinese defenders there greeted them with heavy rifle fire, the Japanese responding immediately in kind. In what were really the first shots of World War II, the Chinese defenders suffered heavy losses, but still managed to hold the bridge. A cease-fire was eventually called, but with even more reinforcements pouring in, the quiet only lasted a matter of hours. Chinese troops continued to harass the Japanese with rifle fire, causing the local Japanese commander to order the shelling of the town.

Tensions remained high as each side continued to reinforce over the coming weeks, with Japanese fury only exacerbated after reports reached their ranks of Chinese troops murdering over a hundred Japanese and Korean civilians following a similar clash in nearby Tongzhou.[9] Once the news spread there was no turning back, the Japanese setting out on a war that was to expand and continue for nearly a decade. Once again, the Japanese outmaneuvered and outfought the Chinese at every turn, and by August 8, they had occupied Peking. By the end of year, their flag had been carried all the way to the Mongolian border in the north and roughly two-hundred miles out to the west, occupying enough territory to establish yet another puppet state named Mengjiang.

The fighting also spread in areas to the south as well, wherever Chinese and Japanese troops were in close proximity. A deadly shootout on August 9 with Chinese guards and an officer of the Special Naval Landing Force in Shanghai caused the Japanese to reinforce the city with 8,000 of their marines. It took less than a week for fighting to break out in the streets between the two enemies. Both sides soon reinforced: the Chinese commander Chiang Kai-Shek sending two of his best divisions to the strategically important city, the Japanese landing three divisions more of their own on the shores to its north. The fighting remained a stalemate over the next several months, but eventually the continual pouring in of Japanese reinforcements finally tipped the balance. By the end of October Japan had seized control of the prized city, winning the first major battle of the Second World War.

Despite the Army General Staff directing that no further expansion was to occur, the Japanese field commanders were all too tempted by the Chinese national capital of Nanking less than two-hundred miles away, hoping its capture would cause their enemy’s government to completely collapse. Disregarding multiple clear orders from Tokyo to the contrary, on November 11, two field armies began a westward advance in a pincer-like movement toward the city. Meeting little resistance from the now-disorganized remnants of the Chinese defenders of Shanghai, both Nipponese armies raced toward the city as fast as possible in hopes of first seizing the prize.

Both breezed through any resistance the Chinese tried to put up, arriving at the city’s gates on December 9. The fighting trying to break into the city was initially intense, but within two days it was clear that it was all over. The Chinese commander issued orders for all remaining units to escape the day following, but then immediately slipped out himself while these orders were still being distributed. Mass panic ensued, with some Chinese forces even firing on one another as they attempted to escape blockades imposed by other friendly troops that had yet to receive the order. Thousands more ditched their uniforms and equipment, attempting to blend in with the population; no few drowned trying to swim across the Yangtze to safety.

Sporadic fighting continued over the next several days, as the Japanese scoured the city in attempts to root out the hiding Chinese soldiers. Civilians were naturally caught up in the act, the Japanese growing increasingly frustrated in their efforts. Soon control was completely lost, if there really ever had been any attempt to maintain it. Chinese prisoners – legitimate or not – were executed in various horrific fashions all across the city, such as those murdered by two Japanese officers who famously held a contest to see who could be the first to kill a hundred people with their swords. Others were burned to death or buried alive. Rapes occurred by the tens of thousands, many in the most horrific fashion, with their victims rarely surviving. Looting and burning was rampant. When frenzy finally abated after roughly six weeks of sheer horror, perhaps as many as 300,000 Chinese lay murdered, along with upwards of 80,000 of the city’s women assaulted in the worst imaginable ways.

The world was horrified. So was Tokyo, who still had not even declared an official war in China. Attempts were made to reign in rogue Japanese forces thereafter, but even still events continued to overcome them, especially after news of the defeat and massacre of 8,000 Japanese at Taierhchwang earlier that Spring. Finally Tokyo gave up and joined their own bandwagon, ordering Hankow to be seized: a city that historically dictated the collapse of Chinese dynasties whenever taken.[10] As they approached in the summer of 1938, Chiang order the dykes holding back the Yellow River to be blown in hopes of channeling the oncoming Japanese into his defenses. That doing so meant the drowning of upwards of a million of his own people in the massive flooding was simply just the cost of war. And an equal number of those that had somehow managed to survive were now forced to find new homes, having lost all of the little they had. How many of these refugees subsequently starved to death or were killed by disease in the months that followed is unknown.

Despite the canalization the flooding forced on them, along with the massive Chinese troop build ups into the dry corresponding defenses, after only a few intense clashes, Chinese morale was broken. The city that so many had given their lives to hold, both willingly and unwillingly, was abandoned to the Japanese on October 25. Citizens both locally and across the world now feared a repeat of Nanking, but this time the Japanese moved in earnest to avoid any further condemnation, entering the city first with a large detachment of military police to ensure order. Thankfully, no such incidents occurred, the occupants spared a repeat of one of the world’s greatest atrocities. What remained of the broken Chinese army retreated once again, this time to Chung-king, a city far beyond the reach of the Japanese. Satisfied at all the territory they had gained, the conflict unofficially settled for the time being.

Although extremely successful in terms of land seized, Japanese losses had also been heavy. Replenishing their depleted ranks however also meant forcing them to expand their service age parameters and to dig into its poorest classes for replacements. As a result, soldier quality, and thus operational performance and capability, was greatly reduced. On top of that, expenditures and losses from the war only added to the demands on industry, setting back Japanese modernization efforts even further. To make matters worse, guerilla raids by communist leader Mao Tse Tung were disrupting much of the shipments of raw materials out of the Asian mainland that were the primary reason for the conflict in the first place. So, while war had been wildly successful in regards to changing boundaries on contemporary maps, the move also only set the Japanese even further behind in their preparation for conflict with the West.

Although they likely did not realize it, Nippon was now caught in a cycle that only increased the possibility of war they were afraid of, for the more areas they invaded for resources, the more it only increased Western disdain. And disdain grew long before any of these exploited resources could be refined and used to manufacture ships, tanks, planes or oil. Seeking to maintain an equal standing with the world’s major powers, while the world quickly closed off trade to them, the Japanese were in actuality only pushing themselves closer towards the very war they were preparing for.

Like it had in the previous war, events in Europe provided another all too tempting opportunity. Resource starved, particularly in oil production, the potential raw war materiel found in Indochina and the Dutch-controlled Indonesian Archipelago lay ripe for the taking after Germany had occupied Holland and France in the summer of 1940. Worried that the Germans – or someone – might assume control once they finished off Great Britain and had time to consolidate, the Japanese moved to join the seemingly unstoppable Axis Powers. Doing so also served to check dangerous Russian aggression, so it was a natural move for Tokyo. Hitler, who saw the opportunity such an alliance presented to force his British and future Soviet enemies to spread their forces out across their empires, approved.

The three nations that were soon to engulf much of the world in flame, the Germans, Italians and Japanese, all signed the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940. Most importantly for the Japanese, the agreement did not require them to enter the war against the British, along with guaranteeing them the much-coveted sole sphere of influence in Asia. Once again, assuming Hitler won, as it fully seemed that summer that he was likely to do, the Japanese were to greatly benefit from joining an alliance without having to actually participate in its far away partner’s conflicts.[11]

Japan now began to move south, initially attempting to manipulate and bully the Vichy French colonial leaders with yet another rogue unit trying to force its national leadership into a more aggressive policy, making an attack in northern Indochina in the Fall of 1940.[12] Little gunfire was exchanged in the encounter, and an agreement was quickly made, but in the end the Japanese were allowed to occupy Tonkin. This cut off a major Chinese supply route and gave Nippon advanced bases it needed in order to put most of Southeast Asia within range of its air power. Support for the Thais a few months later over contested territory in Cambodia and Laos also strong armed the Vichy French, and with little bloodshed, the Japanese now had access to bases in Thailand as well.

Their next move was to try and open trade with the nearby Dutch, their far away home country also occupied by Nazi Germany. Staying loyal to a government that continued to rule in exile, the Dutch refused any concessions to the vulture nation who was allied with the occupiers of their home. Despite all Japanese maneuvering and threats, the Dutch held firm. Denied, yet in desperate need for the oil held in the Dutch East Indies, pushed the Japanese to now consider outright war for the resources their war machine so desperately required.

The moves in Indochina brought the Americans to the point of outright animosity however. Whereas previously all embargoes against Japan had been limited, now the United States refused all exports of any war material whatsoever, although they softened the wording to convey that trade was still technically open, just only for what the Americans deemed they could spare. Even further, they also now began aiding the Chinese militarily, most famously in the form of Claire Chennault’s “Flying Tiger” squadrons. While unofficial and comprised strictly of “volunteers,” American pilots were soon taking to the skies over China in American aircraft and actively engaging the Japanese in combat. As a result, Japanese planning now started to incorporate the idea that should they make any military move in the South Pacific, conflict with the Americans could not be avoided.

With Europe seemingly on the brink of collapse, the United States had begun a program of significant rearmament in the summer of 1940, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt making repeated calls for the America to serve as the “arsenal of democracy” and instituting Lend-Lease programs to arm nations that were to soon become allies in their fight against the Axis. This effort also included military expansion and armaments production for her own use as well, strengthening feelings of the war’s inevitability even more in Japan. As Tokyo looked at Washington, it was not hard for it to see that it would not take long before this growing American power was able to overtake what they had on hand.

Increasingly isolated and feeling surrounded by Western enemies, the Japanese now had two choices to make as the calendar moved through 1941. Their first, as was made crystal clear by the Americans on November 26, was to reduce their military posture, give up their holdings in China, and rejoin the world in peaceful trade. Giving up in China, where Japanese losses now numbered in the hundreds of thousands, along with the invaluable resources captured there necessary for their industry and defense, and then demobilize, was absolutely unthinkable. The Japanese knew just what happened to non-Western nations that were weak, and virtually all of them were now colonies of some form, their affairs dictated to them by a European overseer. Tokyo realized, quite accurately, that achieving equality with the West through peaceful measures was never going to be a real possibility.

Their second option was to expand their war and extend their control throughout eastern Asia and the western Pacific. With Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union that summer clearly seeming to be going in Germany’s favor, Japan’s largest and most immediate threat was now completely preoccupied in a fight for its survival. And with the governments of the various colonies in the region mostly occupied and located all the way on the other side of the world, the territories in the Orient were ripe for the taking. The only matter really in question was what the response of the rearming United States would be to any moves they made.

Although a massive statement of the obvious, perhaps the greatest mistake the Japanese made at this point was to decide to directly attack the Americans. Not widely considered by historians today is that it was quite possible for Japan to have only invaded the Dutch or French colonial territories and not involving the Americans or British. The former was not allied with any of these colonial governments and its populace had very little interest in getting involved in any of the wars overseas, meanwhile the latter was completely on its own and so militarily weakened by the war in Europe that the loss of a small colonial holding in Asia for the Dutch was the very least of their concerns. It was quite possible that the Japanese could have seized the Dutch East Indies without going to war with either of the two.

Despite this glaring reality, Japanese planners continued to look at the growing power of the United States, knowing that they had two, perhaps three years at most, before the Americans were able to overpower them militarily. Beyond that, they could never hope to keep pace with its industrial might. Although caught in the midst of modernization, with its military worn down from a decade-long conflict in China, Japan was being massively unprepared for war on a massive scale. Yet the aggressive traditional Samurai thinking won out over reasoning: with the exception of the Soviet Union, the Japanese made the decision to attack all the Western powers at once. The decision was one of the greatest strategic miscalculations of the entire war.

Planners in Tokyo estimated it would take them until November at the earliest to move troops into position and prepare the decisive attacks they envision across the Pacific. But they also reminded their leaders that with every month that passed thereafter, the Americans were irreversibly growing stronger. The Japanese therefore knew that the window for any hope of military victory against the Allies was closing fast. If they were going to strike, the time was now.

In only a few short months, one of history’s gravest of decisions had been made, as all six Japanese major fleet carriers set sail from Etorofu in the northernmost reaches of Japan, steaming east toward Hawaii. Coincidentally, they went to sea on the same day American Secretary of State Cordell Hull presented the previously mentioned pacification demands for them to continue any peace talks in Washington. Attempts at re-opening trade and relations by the Japanese were to continue up to the very end, but as ships of the Imperial Japanese Navy continued on their journey across the Pacific, a passage that was to change the world forever.

Their desire to preserve their independence and position in the world through military strength had led the Japanese to start the very war they were trying to prepare for in the first place, and long before they had the strength to do it. The army and navy that had achieved fame by defeating a second-rate European power in 1904-05, found itself outdated by the military evolutions of the Great War and was once again forced to play catch up in order to industrialize and meet the demands of 20th Century warfare. In the meantime their army was geared completely towards land campaigns in China, and was worn out by a decade of fighting there.

Yet now Japan decided to start a war against both the world’s leading naval power and its leading industrial power. Moreover, regardless of what they hoped to achieve in its opening salvos, Japan’s strategy beyond its first several months was left blank and up to providence. Dai-Nippon had doomed itself even before any of its aircraft had lifted off its decks that fateful Sunday morning.

[1] Japan is a non-native term to describe the island nation. The official name of the country is日本国, pronounced “Nippon-koku,” or the State of Japan, and “Nippon” is used primarily by the Japanese in everyday speech and writing. Translated directly, it means the “origin of the sun,” and thus the nation is often referred to as the Land of the Rising Sun.

[2] Present-day Taiwan, one of the ninety islands that make up the Pescadores Islands archipelago.

[3] Of note, as the European powers colonized the world, no other non-Western nation in world history so successfully anticipated their threat, modernized and expanded as did the Japanese, attempting to make themselves equals in order to preserve their independence.

[4] Some historians have referred to the Russo-Japanese War as World War Zero, given the close similarities between it and what was soon to be seen on the battlefields of Western Europe less than a decade later.

[5] The Treaty of Portsmouth was successfully brokered by US President Theodore Roosevelt Jr., for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906.

[6] The Japanese were to meet many from this same production run of ships at Pearl Harbor.

[7] Private Shimura Kikujiro claimed to have been having stomach problems and had become lost in the darkness as he went to relieve himself.

[8] Peking is now more commonly referred to as Beijing.

[9] Tongzhou is a district of Peking.

[10] Similar to the cities of Buda and Pest that make up the singular Hungarian capital today, Hangkow is one of three distinct towns divided by the Han and Yangtze Rivers, collectively referred to as Wuhan.

[11] This move also provided some reassurances regarding conflict with the Soviet Union. Although not guaranteed, the Japanese were now officially allied with Germany, who at the time was a signatory member of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Japanese hoped that peace would extend, through these agreements, indirectly to them as well.

[12] Present-day Vietnam.