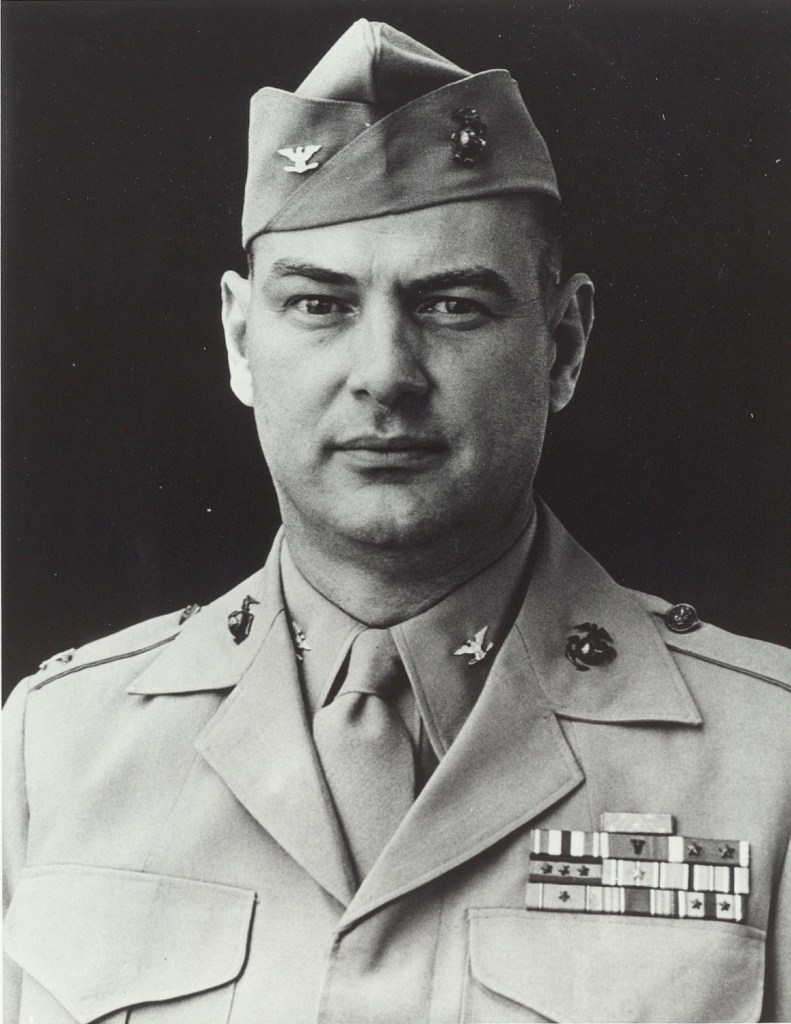

LtCol. Justice Chambers

Born February 2, 1908 in Huntington, West Virginia, Chambers enlisted in the US Navy Reserve in 1928, then signed on again in the Marines as a Private in 1930. He earned an officer’s commission two years later, serving in the reserves until he was activated in 1940.

A captain in the 5th Marines when the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, he soon volunteered to serve in a new type of Marine unit, one styled after the British commandos in Europe. Named for its commanding officer, the Edson’s Raiders were soon shipped overseas, serving first as a guard unit in American Samoa.

There and at New Caledonia, Chambers trained the men of his E Company hard, expecting the machine gunners and mortarmen of the weapons company to move as quick and as light as any of the battalion’s rifle companies – men who as Raiders were already expected to move at more than double the speed of regular Marine infantry. “I had made up my mind that they were going to be as mobile and able to get around as a rifle company,” he once stated.

On August 7, Edson’s Raiders made a surprise landing on the island of Tulagi, just hours before the larger Marine force made its landing on Guadalcanal just a few miles to its south. Hoping to surprise the Japanese, the Raiders attempted to move so rapidly across the mile-long island that they secured it before any of its defenders even had a chance to react. They made it two-thirds of the way.

Japanese resistance stiffening, Chambers pushed his men to keep their momentum going. As he did, he was struck by what he suspected was a Japanese mortar round that exploded nearby, shattering both his wrists and gashing his left leg. The blast also left a sizeable a piece of shrapnel embedded in his kneecap, causing him severe pain whenever he tried to walk as its sharp metal edges cut further into his flesh with each and every step. Despite the extreme discomfort, Chambers refused to be evacuated until his company had swept across the remainder of the island, finally reaching its eastern-most shore just before sundown – likely the entire time without anesthetics.

Handing over command, he moved to an aid station near their initial landing site, but many displaced Japanese that they had bypassed during their rapid advance were still active and trying to reorganize across the island. Hearing all kinds of noises and chatter in the jungle around them, only a few in the aid station were in any sort of fighting condition, and even these were mostly armed with Japanese souvenirs they had picked up and were hoping to bring home. Chambers knew the men he was with would be slaughtered if they were attacked, so when Edson happened by to check on him, Chambers implored him to move. The Raider commander agreed, and his entourage helped them move the wounded along a trail up a hillside nearby. The new location was better, but still precarious.

After midnight a back and forth mortar battle started up, with each side lobbing rounds at each other out into the darkness. The Marines had the advantage of being higher up on the hill and firing down on the Japanese in the jungle below, but still the enemy rounds could be just as deadly. Unable to move and with only white Navy blankets for protection, those in the new aid station found themselves helpless in the middle of it, unable to do anything but to lay there out in the open and hope none struck among them.

Time stood still as they waited in horror, then the Japanese attacked. The few with weapons managed to fight them off initially, but the nearest Marines on the hill above did not know the makeshift aid station was even there. Seeing the enemy fire below, most of it making the distinct sounds of Japanese weapons, the Marines began firing both at and through them. Seeing what was happening, the wounded Chambers quickly organized the evacuation of the group, sending them further up the trail into the pitch black darkness. Many had to be carried out on stretchers by a few brave Corpsmen who made the trip several times. The last out, Chambers led the displaced wounded until they finally ran into another Marine unit and were able to move behind them for protection. For his leadership that night, despite his own severe wounds, undoubtedly saving the lives of the dozens of helpless and wounded men, Chambers was awarded the Silver Star.

It took him until January 1943 to recover from his wounds. He fought to be assigned once again to a combat unit. His timing could not have been any better. When the 23rd Marine Regiment was split to stand up the 25th Marines in May 1943, Chambers was given command of its 3rd Battalion.

The only reserve officer in the regiment, the pressure on him was extremely high, but Chambers had every intention of bringing the same tough training style he used in the Raiders to his newly created battalion. “What I was trying to do,” he later recalled, “was to make the men’s lives so damned miserable in training that when they got into combat the only thing they had to worry about was the enemy.”

Many could not hack it. But before long the 3rd Battalion had created a reputation for being the hardest-trained, most aggressive, most out-of-the-box thinking battalion in the regiment – the outfit senior commanders knew could always counted to tackle the toughest of assignments.

The battalion came to realize who they were as well, christening themselves: “Chambers’ Raiders.”